Thank you for your interest in this site. Please note that all images are copyright protected and not available for use without permission. Please contact journeys@tenthousandcranes.com for any inquiries about the information contained in this site.

____________________________________________________________

The Great Wall had not been high on my priority list, but I am certainly glad I had the opportunity to visit it, for it was a much more meaningful experience than I thought it would be.

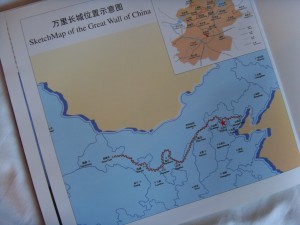

Actually, there is no ONE Wall, but rather many segments of walls built at different times to fend off different warring neighbors. This 5,660 km miracle rides the ridgeline through deserts, grasslands, and mountains. Begun around the 7th Century BC, the various sections were unified by the Great Emperor Qin Shi Huang, the same emperor who had the terra cotta army constructed to protect him in his afterlife.

To be able to actually see stone rather than just a sea of multi-colored T-shirts and the accents that go with them, I was driven for three hours outside of Beijing to visit less touristy parts of the Wall. My recently reconstructed achilles tendon wasn’t up for the task of strenuous treks in more challenging parts of the Wall, so I did a portion of the Wall at Simitai.

Underemployed farmers are today’s first line of defense surrounding the Wall. They are very poor and rely on almost bludgeoning the tourists with their for sale souvenirs. It is their livelihood, but from the moment you debark your bus or car, you are beset with catcalls: “Lady, Gleat Wall T-shilts,” “Ice Cleam,” “hats.” If you so much as make eye contact, you’ve lost.

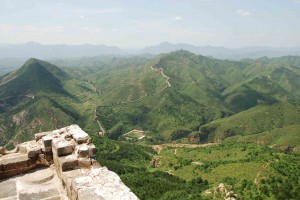

I made it through the gauntlet of hawkers and soon found myself on a magic carpet ride up the mountainside. I don’t usually like gondolas or cable cars and tend to avoid them, but close to 100 degree heat/humidity and a stiff vertical climb were good motivators and I found the gondolas looking mighty fine. I rode partway up the mountain and was quickly captivated by the beauty of the sprawling green hills and farmland spanning most of the area.

The cable runs very slowly, so the ascent took about 23 minutes, taking me closer to portions of the Wall and its towers. I “oohed” and “ahhed” to myself and snapped away. Not only was the Wall captivating as it came in and out of viewing range, but so was the valley below with its terraces of corn and other crops. Corn is the local staple, grown as a dryland crop without irrigation, and little plots were strategically placed anywhere a farmer had been able to carve out sufficient semi-horizontal space for planting. It looked amazingly healthy. I marveled also at China’s effectiveness at stabilizing the hillsides with the small plugs of plant material drilled into the rock. In time this root system should help anchor the quickly eroding mountainsides.

Fortunately (or unfortunately) the gondola car does not go all the way up the mountain to the Wall itself, so one must endeavor and sweat to earn the right of passage. I dismounted the still-in-motion gondola quickly, since it neither slows nor stops for mere mortals, much like the cars, busses, and taxis in city traffic. If I wanted to make anything more of this experience, I needed to start climbing straight up, which I did. Within minutes I was a dripping mass and my knees were quivering. The steps and concrete of the pathway were irregular as they zigzagged up very vertical cliff faces, crowned by Wall and towers high above me.

Some of the more fit tourists flew by me, but most found themselves clinging to the rocksides or chain railing gasping for breath, faces flush with sweat and fingers puffy from whatever it is that happens to our bodies in this process of prolific exertion and dehydration. I finally succumbed to one of the locals. They are surely cousins to the hawkers and they hang out in the shade playing cards (one of the most common pastimes in rural areas), waiting for wobbly, panting tourists to struggle by, whereupon they suddenly appear at your side and become your best friend. It’s hard, if not impossible, to shake them off. Ignoring them doesn’t help and because outrunning them would be like escaping from a Sherpa on the way to Everest, they are yours for the duration. The expectation is that on the descent, you will buy souvenirs hidden in their little rucksacks, but those not forewarned by Lonely Planet or some other source are unaware of the philandering that awaits them and the inescapability from the photo books, fans, and little ceramic replicas of the Great Wall. You might even be fortunate enough to buy the very fan that was used to keep you alive on your ascent.

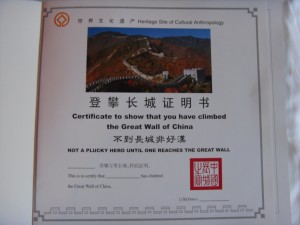

So I was followed up the route to the Wall, fanned at intervals and chatted to at others. My local was actually a delightful woman, mother of two, married to a poor farmer (who could just as easily have been playing cards in the shade rather than out tilling corn, for all I knew). I made it to the top finally, proud of my aging prowess, in spite of my not having tackled a more strenuous course. I arrived at Tower 8, climbed the Wall down to 7 and then up to 9. The views were breathtaking and the magnitude of the achievement of the Wall really sunk in.

As a reflection of Chinese ingenuity, the Wall was built of local materials by local workers to maintain easier regionalized quality control and troubleshooting. For the most part, it was constructed of stone, usually granite. Some of the more desert, westernmost parts of the wall, however, are made of rammed earth and a straw-like material encased in a stucco/mud. Dimensions and styles of the Wall and its watchtowers vary greatly depending on locale. Multi-storied towers dot the eastern sections, while turrets are more common in the more deserty west. Some towers served as message centers (fire and smoke signals), while others served as warehouses. Certain Wall widths were wide enough to accommodate 5 horses or 10 soldiers abreast. Think about that, given some sections were built literally on razor-point edges with nothing but steep drops on either side. One western part of the Wall is inscribed with Chinese characters that say “Formidable pass under heaven.” That’s an apt statement.

Other sections espouse unusual building styles, driven by need mostly. The Simitai section I climbed contains single and double walls, some trapezoidal in shape to keep them stable atop a precarious ridge. One section sits on such a razor-sharp edge that is narrows to what is called “Sky Ladder.” A nearby section is made of stone bricks, etched with dates and code numbers of the armies who made them.

There are segments of the Wall that include great stone temples, battlements, barracks, and even moats, all looking “formidable and elegant at once,” as one of the souvenir books I was suckered into buying says. At places, the Wall stands proud at 17 meters (yes, that’s meters, not feet) and towers were placed strategically at 60- to 200-foot intervals, enabling observers to sight oncoming trouble and reinforcements to shift from segment to segment with ease. Invaders simply could not penetrate or climb the massive Wall, rendering the aggressors largely ineffective at maneuvering horse troops or armies into those protected regions of dynastic China.

I cannot conceive of how the building materials were kept in supply and portered to such inaccessible heights and locations. There must have been armies of workers camped on the hillsides, all needing not only stone to set, but food for sustenance. How this was choreographed is sufficient miracle in and of itself.

In centuries past, untold blood was shed at this impenetrable snake-like fortress. Today, however, it lies like a true crown on China’s head. It is China’s special dragon and it lures millions to its essence. Photographers long to capture a part of this dragon, hoping their lens will make it even more magical than it already is.