Thank you for your interest in this site. Please note that all images are copyright protected and not available for use without permission. Please contact journeys@tenthousandcranes.com for any inquiries about the information contained in this site. These blog posts appear in reverse order (due to my lack of skill in figuring out how to reorder them!).

_____________________________________________________________

Join a specially designed trip to Peru / Bolivia this summer. See TRAVEL category.

_____________________________________________________________

Six different stories from China have been posted herein. They are posted in reverse order, so if you desire to read them chronologically, you might wish to scroll all the way down and read them in reverse order. Apologies for my lack of posting savvy in knowing how to reorganize them. Remaining stories about my continued journeys along the Karakoram Highway toward Pakistan and about travel through northern Xinjiang to Altai/Russia and back to the Silk Road via Hami and Turpan have not yet been posted.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________

Back Tracking a Moment to Where I’ve Been and Setting the Stage for the West

Let me take just a moment to give you some sense of where I am and where I have been. Let’s draw a mental map juxtaposing the U.S. and China. China and the U.S. are similar in continental land mass size, though certainly not in population, wherein China weighs in at 1.3 billion compared to around 300 million for the US, a considerable difference. If we overlay the two maps, we could say I’ve zigged and zagged my way around the eastern coast and the Midwest, from the south to the north. That was the first part of my journey around inner China or Mainland China. The other half of China in the west is comprised largely of several provinces and two sizeable areas: the mountainous south formerly known as Tibet and a mostly desert north called Xinjiang (“x’s” are pronounced like “sh”). So after my exploration of the east, I then headed due west, traversing the east / west span of China to land in this northern quadrant of China officially called Xinjiang Autonomous Region (AR), one of several Autonomous Regions in China. AR’s are names given to those areas wrapped into China that are comprised of mostly culturally different, non-Han Chinese people. Tibet is another autonomous region, called Xizang Tibetan Autonomous Region to acknowledge the Tibetan people and culture, as is Inner Mongolia, but both regions are considered an official part of China and are not independent entities. The same is true for Xinjiang, which is far more like Central Asia than mainland China.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

The Silk Road

The ancient Silk Road connected China to the Mediterranean via mostly camel caravan. It was yesteryear’s internet and eBay, all rolled into one. Just as there was no one Great Wall, there was also no single Silk Road, but rather a series of routes over deserts, mountains, and other challenging transit points. Goods and communication were transported by a vast array of camel caravans, doing segments of the journey. Caravans in one region would complete one leg of the journey and sell goods to another caravan, continuing this exchange and connecting disparate parts of the world. The entire route connected Eastern China to Rome, an unbelievable feat through unyielding terrain and often warring cultures.

It was the Silk Road that brought Islam into Buddhist China along routes that traversed Central Asia and Pakistan before spanning through the Middle East and touching in with Rome. In China, the Silk Road began in Xi’an (remember that “sh” sound), which we could say is perhaps the Chicago of China. Xi’an was an ancient capital of many Chinese emperors, but was also the historic city that linked East with West. I loved Xi’an, partly because I was finally able to escape the humidity and partly because it was terribly exciting to see the cultural mix where Islam literally meets Buddhism. I found Xi’an’s Muslim Quarter fascinating and was able to dive into my own vegetarian version of skewered, bbq’d vegetables while the rest dined on lamb.

Makeshift captions: Xi’an Muslim Quarter by night: Terra Cotta Warriors

————————————————————-

From Xi’an west, the landscape begins to change, as eventual deserts take over the vast agricultural lands of eastern China. Towns ultimately become more sparse, situated around desert oases. I have flown, trained, and driven through part of this terrain and am awed when I transport myself back in time to the era of caravans.

In the West

Urumqi (“q’s” are pronounced like “ch”) is the capital of Xinjiang AR and has served as my tether point in the West. The city is hustling and bustling and is an intriguing cultural mix of primarily Han Chinese settlers and original Uyghur people (Wee gurr is the easiest way to give a sense of pronunciation for Uyghur), though it is also loaded with Mongols and other Central Asian peoples (think all those countries ending in “stan”). Xinjiang itself is split into deserts and mountains. Trending from north to south, picture first mountains, then a large desert basin (the Yanggar Basin in the western extension of the Gobi Desert), another range of mountains, another desert basin (the Tarim Basin of the Taklamakan Desert), and then more mountains continuing to give rise to the massive Tibetan Plateau (mostly Tibet) leading to the Himalayas. If that made any sense, you don’t’ need to pull out a map, though a map would make this lots easier. I’ll see if I can grab one from Wikipedia to insert in this post. Urumqi sits in the southern part of the first desert basin I described. North of Urumqi lie spectacular grasslands, more typical of what we might associate with nomadic Mongols or Kazakhs. I head there next week.

Red on map shows Xinjiang AR; others give some sense of deserts and mountains

————————————————————

In order to experience more of this Muslim part of China and the Central Asian aspects of this region, I wanted to head down to another leg of the Silk Road, the Southern Silk Road. So driver, guide, and I headed south, crossing first through the mountains and passing through one of China’s large wind farms. We stopped at several regional towns/villages along the way and I, of course, have fallen in love with western China. This is a region of donkey carts and bazaars. All life takes place in the markets and bazaars where all items of exchange are displayed while donkeys, motorcycles, cars, and traditionally attired people walk the crowded paths to barter, socialize, flirt, and swat flies. It was one of those “other world” sorts of experiences, where I found myself walking amidst lambs on their way to new homes, children lulled to sleep by the hot sun sprawled on and under carts, and tired mules left to stand while the hub of humanity buzzed around them. At the same time, I was surrounded by colorful fruits, nuts, and vegetables, where sampling was encouraged and the juice of sweet melon ran down my arms.

Urumqi transportation; bazaar scenes

———————————————————–

While I had the camera in hand to capture images of those different from myself, I was more the object of stares. I passed no other westerners at the bazaar. In general, the people were exceedingly warm, allowing me to photograph them in all states of their market process. I have found that taking photos of a group of young boys is usually the way to break into a crowd. If I could engage them and show them their digital images, others were usually willing to be photographed. Wherever we stopped to enquire about an item for sale, the crowds immediately gathered to listen to the language of the tall foreign woman ! My guide said she would see me stop, momentarily seeing my shoes, and then within the next minute, couldn’t see my shoes at all since they were lost in a sea of local footwear. I could do little without her, however, since English was rare.

Bazaar scenes

————————————————————-

The highlight of my time in the towns in the northern part of the Tarim Basin was meeting my guide’s family, who spent the day taking me to the local bazaars, buying vegetables and nan bread that they would later turn into one of the most delicious meals I’ve had in all of China. Being guest of honor amidst such a loving and beautiful family was an experience I will not top anywhere else on this trip. My guide is Uyghur, so meeting her family and visiting her home was an unexpected bonus on this trip. My meager gift of cookies for all of the awaiting children was a small offering for the experience I was given in return. I had been invited to spend the night with the family, an opportunity I was so looking forward to, but it seems their village was not one of the villages approved to host foreigners, so the overnight did not happen.

Proud Grandmother

———————————————————–

The next day we began our journey across the Taklamakan Desert, fortunately by car rather than camel. We were blessed initially in that the day was overcast, protecting us from the relentless desert heat. But we were not able to escape the winds that harangue the deserts and move unfathomable amounts of sand and particulate across the landscape at random. I gained a profound appreciation for desert life. The sand is really a powder and no barrier prevents its entry. L’Oreal Mineral Powder cosmetic has nothing on the fine coating of dust that covered every exposed part of my body and more. The sandy powder coats one’s eyes and nostrils and covers everything in one’s possession with a fine film of powder. There were no rest stops along the five-hour route we took, so pit stops involved heading into the pummeling wind across the sands while a choking, fine blast of sand threatened to topple us over. I know now why desert women wear skirts and scarves.

The Desert; a hut in the middle of nowhere (before the sandstorm !); stabilization grid.

———————————————————–

But I wouldn’t have missed this experience for anything, in spite of the screaming that went on inside my head, begging for the winds to stop and the sand to settle into otherwise beautiful dunes. My respect for the millions who have trod the desert paths throughout millennia increased multifold and I tried hard to grasp what it must have been like to be part of an endless procession of carts, carpets, and livestock crossing these vast spaces of nothingness, inhospitable in the best of circumstances and only marginally survivable under the worst. A highlight was seeing three wild camels emerge from nowhere and beat their way through the blowing sands. I could not imagine that any one spot was better than another, so wondered what mission called them to be roaming about in such winds. And I know our winds were mild compared to what the desert can dish out. Development of oil fields has brought life and asphalt to the Taklamakan, but its historic name of the “Death Sea” is still apt.

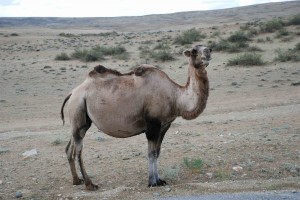

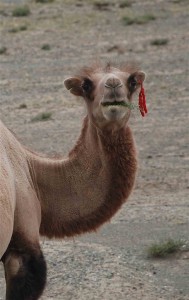

Camels shown are from the Gobi Desert

The end of the desert brought us to Hotan, one of the most vibrant towns along the route. We spent the day first at a silk factory, where I saw the making of silk, from the caterpillared capsules that are then boiled to extract the fine silk fibers to the tedious weaving by tired and dirty hands and feet. Adjacent is a silk carpet-making area, where looms and beautiful carpets tempted me, but neither budget nor luggage space could accommodate such extravagance, even at those prices. My guide knew of a hand-made paper-making place where the tradition of making paper from mulberry tree skins has been passed on for years.

Silk Spinning; lovely girls at the bazaar

———————————————————–

We will head out to the market bazaar soon, after a bit of an afternoon rest that allowed me to type up this brief sketch of some recent experiences. I am blessed with the best driver and guide who are giving me such an incredible taste of Xinjiang. Stay tuned, for the journey continues. Tomorrow we head to Kashgar in preparation for the largest regional market and a later taste of the mountains that separate western China from Pakistan.

Typical street and bazaar scenes

————————————————————

Onward To Kashgar

Heading west again across the southern rim of the Taklamakan Desert wove us in and out of desert land, oases, and villages. I have not yet figured out how to describe villages and their constant hum of life, but suggest you imagine whitened-beige adobe walls surrounded by the green blessings brought forth by various streams and rivers draining north toward the desert from the Kunlun Shan Mountains of the northernmost edge of the Tibetan Plateau (ok, so that got a little bit too geographic in its detail !). The adobe walls are broken only by a single front door, which is really more a large gate leading into a courtyard, from which the various rooms of the dwellings fan out. Some doors are ornate metal in their Central Asian decoration, while others are of weathered, sagging wood. Glimpses in often revealed a woman with broom, a pantless child, or several chickens. I felt both compelled to peak, yet circumspect enough to avoid invasion of privacy. My camera, however, yearned always to stand in the doorway.

Many of these homes are also businesses, so one might find motorcycle repair in the front yard, peach sales by the road side, or a cooler with cold drinks outside another. Donkey carts and cars vie for space on the roads, children dart about, and women in headscarves work busily at one task after another. There is often music playing from a central loudspeaker, accompanied by braying and endless horn honking. This goes on for blocks, while males in hats stand in small man-groups discussing the business of men and other children slip naked into water ditches to cool themselves from the heat. The villages are old, parched by poverty and desert, but remain Old World vibrant and exciting.

Our village interludes were interlinked by what I would call one of the worst roads in China (though I know it is not). It was paved, but pocked and bouncier than any four-wheel road I’ve experienced. Women who travel this road gain a bra size within the first hour, and not in a pretty sort of way ! Our mini, mini-van didn’t have the best shocks in the world, so about ten hours of this did not leave me blessing China’s division of road engineering. It was interesting to note, however, that a partial new road was being prepped parallel to our two-lane to make the frenzied road jockeying without rules a bit less hair raising with separated directional lanes. I know it is not easy to maintain roads under harsh desert conditions, but this was not the total desert crossing of our previous journey across the “Death Sea” and this was a heavily traveled commercial route that surely has already cost thousands of truck drivers their lower backs and kidneys.

Our last stop before Kashgar was Yengisar, knife-making center of Xinjiang. All the knives were handmade, adorned with decorative handles of metal (some precious metals, even), bone, or antler. I could not think of any one of my family or friends who might enjoy a 10-inch animal skinning knife as a gift, decoration or not, so passed on a purchase, much to the dismay of the expectant shop owner. Apologies if I forgot about someone’s special interests.

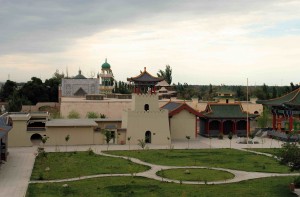

Kashgar itself is the second largest city in Xinjiang. Because this region lies at Xinjiang’s extreme western edge, it has been a melting pot of cultures from Uyghur, Kirgiz, and Kazakh to Tajik, Uzbek, Hui (Muslim Chinese) and Han settlers. It is the crossroads of the Northern and Southern Silk Roads, each having crossed different desert parts to meet in Kashgar before taking other Silk Road routes through Pakistan or Central Asia. Kashgar holds Xinjiang’s largest mosque (and probably China’s largest), but a mere 40 km away lies the Three Immortals Cave, an 1800-year-old relic of Buddhism.

Kashgar Welcome sign; Id Kah Mosque

———————————————————–

Kashgar is known for its Sunday Market, especially the Livestock Market, wherein thousands of animals are brought to the market by certain families, via truck, cart, or hand led, and go home with other families, save the unfortunate few who found themselves on skewers to feed the hungry masses of traders. The market is one of the largest in the region, so large I gave up on seeing it all. I knew the livestock part would be hard for me to witness, and it was. Animals are the mainstay of these people, providing food, transport, and hide. I tried hard to push my Western precepts out of the way and was mostly successful, but do recall giving one man a less than pleasant look at his neglect of a gagging lamb in a too-tight tether (it is common to loop one rope around the continuous necks of many sheep, such that if one tugs in a different direction, it tightens the rope around the one next to it). My friend/driver politely pointed out the man’s errant way, and the rope was loosened. My look didn’t endear uninvited Westerners, however, and I wisely opted to keep my camera momentarily at rest (photo image is of a different man and his sheep).

The market is sectioned off into different animal types, divided only by the various groups of seriously examining and bartering buyers and sellers. The sheep are first and most plentiful, given mutton is the primary food of the entire AR. Goats, cattle, donkeys, and horses round out the rest of the livestock portion of the market, with donkeys and horses taken for test drives much like a car from the BMW showroom floor. Successful buyers pack, tie down, tether, and carry their new purchases homeward, amidst a cacophony of brays, moos, bleats, and horns. It was disturbing to see how carelessly and casually the livestock were handled, given the role these animals play in the lives of the people. Animals stood tied awkwardly and uncomfortably in the beating sun, panting and submissive in their fate.

On the other hand, I knew I was witnessing an ancient market tradition, one that was the lifeblood of the people and had allowed for their survival for thousands of years. Sweet melon, kabobs, and watermelon fed the enterprising crowds, and boys became men as they sold their first goat or helped aging fathers round up stray donkeys who had escaped amidst the bargaining.

I wish I had time to visit the Tajik village in Tashkorgan Tajik Autonomous County, where wild animals are revered and never killed, domestic animals are never beaten or kicked, and horseback riders never ride through the middle of a flock of sheep. Tomorrow we are to venture up into the spectacular Pamirs toward this Tajik region, so possibly I will have a taste of this experience with some of the lower lying Tajik people, often called the Eagles of the Highland.

Xinjiang continues to be a remarkable place. I would love to experience a full year of seasons amidst its beauty, watching the golds and reds of Autumn overtake the green oases and grasslands, seeing snow blanket the mountains and their otherwise resplendent valleys, and witnessing the re-emergence of life with the Spring pulse. I will never forget the people of the south, in their hats and head scarves, lips breaking into smiles, eyes already narrowed by years of sun, and skin weathered and toughened by arid skies. I find their tenacity, their vibrancy, and their warm pragmatism endearing.

After this time on the Southern Silk Road, we return north to Urumqi, where the plan is to visit just a bit more of the Northern Silk Road before heading northwest through the grasslands toward Kazakhstan, where Mongol and Kazakh herders dot the grassy and wild-flowered landscape with yurts and livestock.

The following are images from stories not yet written.

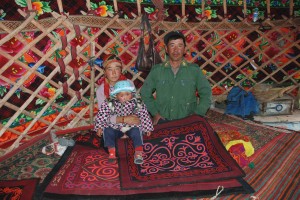

Journey up the Karakoram Highway to Pakistan; Kyrghiz family and yurt

___________________________________________________________________________________________

Grasslands of northern Xinjiang, land of Mongol and Kazakh nomads

__________________________________________________________________________________________

Kanas River and Reserve, Altai, border area of China/Russia; sunflower fields of northern Xinjiang

_______________________________________________________________________________________________

Kazakh camel; Hami (note architectural blend of Islamic and traditional Chinese influences)

___________________________________________________________________________________________