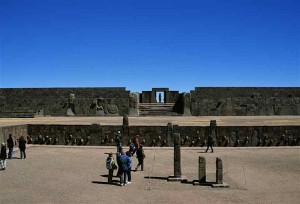

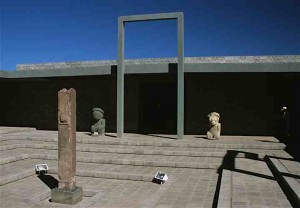

Tiahuanaca ruins

Thank you for your interest in this site. Please note that all images are copyright protected and not available for use without permission. Please contact journeys@tenthousandcranes.com for any inquiries about the information contained in this site.

_________________________

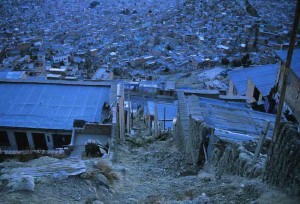

La Paz: City in the Sky

One gasps upon flying into this city in a bowl. Lying at a sobering 11,942 feet in elevation (3,640 m), La Paz and its two million people are stuffed tightly into a canyon amidst the jagged Bolivian Andes. It is a city seemingly painted onto the valley floor, spreading precariously up the hillsides in a checkered array of color and adobe.

Dawn over the hillsides of La Paz (see Squatters story)

El Alto, its suburb and international airport host, hovers proudly at 13,615 feet (4150 m), while 20,741 feet (6,322 m) saintly Mt. Illimani stands sentry overhead. There is no moment in La Paz when one loses sight of the heights at which this city is perched.

La Paz’s alleys and byways hum with the oozing of commerce and poverty. Shop doorways open abruptly onto narrow sidewalks, while small cars maneuver cobbled streets like frenzied wind-up toys. Much of the developing world is a mosaic of color and La Paz is no exception. Red is everywhere, pulsing the blood of Bolivia through its narrowed arteries in sprays of crimson shawls, hats, and vests. The brujas at their Witches Market sell herbs and talismans in brilliant red and green bags and the cityscape hums with yellows, pinks, and greens.

La Paz outgrew itself years ago and its largely indigenous population in this capital seat feels pinched and squeezed between the mountains and the ruling elite, both of whom dictate conditions of life for these Aymara people without consultation.

But Bolivia lacks options. Much of its terrain is comprised of the mountainous Cordillera or the stunning but barren Altiplano, a vast high plateau second only to that of Tibet’s in expanse. The Atacama Desert lies to the southwest, niching itself as the driest place on Earth, while salt flats from paleo lakes comprise much of the south. The yungas is the rainforest of the east. Bolivia lost its coastal extension to Chile in the late 1900’s, adding it to the list of impoverished landlocked countries around the world. The country’s landscape is spectacular at all turns, breathtaking in its juxtaposition of sky and land, but woefully lacking in hospitality.

Bolivia’s economy is one of South America’s poorest. Since independence in 1825, Bolivia has been convulsed by over 200 coups. None of the five presidents from 1999 to 2005 was able to improve the lot of the poor, who finally took to the streets several years ago with paralyzing effectiveness, calling for new presidential elections, the nationalization of gas and oil industries, and a more even distribution of wealth. This wave of unrest ultimately led to the election of Bolivia’s first indigenous leader, Evo Morales, who spouts a socialist platform, mentored by Venezuela’s Chavez and Cuba’s Castro. The 60% indigenous population is largely stitched into a landscape barely able to support them.

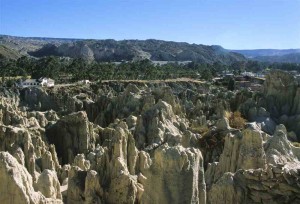

- Valle de la Luna, the Badlands of La Paz

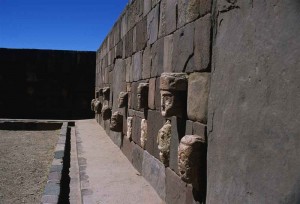

- Just another brick in the wall – Tiahuanaca

- Tiahuanaca

Tiahuanca

- Dusk settling over the Altiplano

Driving in Lima

Latin American cities in general are patterned after traditional Spanish layouts, anchored by a primary central plaza linked to a series of smaller outlying plazas, all of which form the hub of residential and commercial life. It is about community and efficiency. And it is not uncommon to see one’s waiter from a small restaurant scurry to the nearest mercado in search of the very greens just ordered. This communal efficiency plays out in surprising ways.

Since Lima is the international arrival point for travelers to Peru, the government has made a concerted effort over the last decade to spit polish the city some. Many sectors have been improved and revitalized, creating a fresher look for the 8 million who dwell there.

The government still has much to do, however, in the area of traffic control. In Lima, traffic lights are more decorative than functional, and mere negotiation down streets requires a skill that few of us possess. Not only do Latin Americans use the metric system, they use it in driving, giving undue credence to millimeters as sufficient distance between vehicles to allow for passage.

In the U.S., we complain about rush hour gridlock; in Lima gridlock is an all-day exercise in crawling, squeezing, and outmaneuvering. The ultimate weapon is, of course, the horn, an aspect of driving whose logic escapes those of us trained that horns are emergency tools, not requirements for movement. To add to the clamor, small buses (which are really vans) noisily travel the streets with two paid staff: the driver with one hand on the horn and the “caller,” poised with either head or entire body out the window or door, continuously yelling out destinations and stops.

If the goal of the caller is to be loud, the goal of the passengers is to pack themselves in the vans like injection foam in a crate. On the edges of the city, the added trick is also to pack in your chickens, small portions of your crop, and about four children each. In Lima we saw fewer chickens.

In spite of the cacophony of noise and the maze of vehicles, accompanied by carts and bicycles vying for street space, traffic functions with a rather unusual form of communal efficiency. It is as if some mastermind hovers above the city, turning the squares on the Rubik’s Cube such that all vehicles get to where they want to go.