[This is part of a series from the South America Compilation.]

Thank you for your interest in this site. Please note that all images are copyright protected and not available for use without permission. Please contact journeys@tenthousandcranes.com for any inquiries about the information contained in this site.

Thank you for your interest in this site. Please note that all images are copyright protected and not available for use without permission. Please contact journeys@tenthousandcranes.com for any inquiries about the information contained in this site.

___________________________

By day, they are invisible, scattered about the city like stray dogs on the prowl, digging through yesterday’s trash, begging outside of restaurants, or sleeping in the ragpiles of cardboard and debris. But as creatures of the night, they regroup, claiming the streets as their own, clinging together for warmth and safety, forgetting the curses and whimpers of their days. This is their moment of grace, when darkness permits brief respite from their lives.

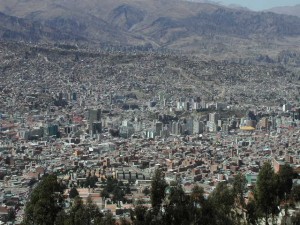

These are los abandonados, the abandoned children of La Paz. Lying at a sobering 11,942 feet in elevation (3,640 m), La Paz and its two million people are stuffed tightly into a canyon amidst the jagged Bolivian Andes. Bolivia’s economy is one of South America’s poorest, so it is no wonder that thousands of the world’s 150 million homeless children roam the streets of La Paz. In bandanas and hoodies, they work the streets by day, begging, shoe shining, or hustling food.

I teach Cultural Geography and was leading a small group of travelers through parts of South America. I had asked a Bolivian friend of mine who had written about street children if we could meet with some of these kids. She had arranged for Eduardo, one of her research assistants who often talked with the kids, to take us out one night. We met at 10:00 PM. The streets of La Paz still bustled with the remains of the evening’s activities: people emptied from restaurants, closed down street stalls, or strolled the plaza walks.

Eduardo explained that most street kids are orphaned by fate or choice. Some, products of shacks or crumbling stucco, come from families where fathers are dead, missing, or just plain mean. Many men, lost in the wreckage of their own failed manhood, abandon wives and children for the bottle. Mothers, left with a brood to feed, are often too poor, too sick, too beaten to make much of a blip on life’s radar. Most of them labor by scrubbing whatever needs scrubbed, selling whatever the trash might yield, or offering their prematurely aged bodies up for whatever form of commerce might find them useful. With too many mouths to feed, the women have no choice but to send their children out to the streets to beg or permanently fend for themselves. Other children have exiled themselves onto the streets, fleeing abuse and wanton neglect. The majority have been left as discards – by death or abandonment – with nothing but the streets.

Girls and boys from three to twenty live on the streets. These are not squatters living in makeshift homes; these are children who live literally on the streets. Eduardo was introducing us to a group of about seven boys. From a distance, they appeared mildly animated, laughing amongst themselves. Eduardo approached them, explaining our mission. They were wary, used to being ignored, beaten or chased, and not at all used to an invitation to talk.

It was awkward at first. We were all profoundly aware of how trite the typical “How are you?” greetings would sound under these circumstances. Just what should one’s opening line be when meeting the “pox” of the streets? After some awkward smiles, some of us pushed forward the bags of food we had been clutching, offering them like pass cards to conversation.

The boys were short, for the most part, with skin darkened by lineage and dirt. High cheeked like their ancestors, they were dressed in pants of all sizes and worn out shoes. Their thin, torn jackets and stained sweaters didn’t seem much protection from the cold. Their faces, shrouded by hats and hoods and night, were still childishly handsome. One had a two-inch scar running from his left eye toward his ear; it was the whitest part of his face. Snot ran from one boy’s nose, the signature snot of poverty, glistening in street lamps when he turned his head a certain way. I couldn’t see the lice, but knew they were there, thriving in the mobs of coarse, dark hair.

One boy sat on a bench, dangling his foot in a silent, circling motion. I was momentarily distracted by the laceless shoe, missing its tongue and most of its sole, but graceful in its solo dance. I stood in the comfort of my hiking boots, wondering how my polished toenails would fare sticking out from that torn remnant of a shoe.

The only one of my group who spoke Spanish, I explained my interest in understanding different parts of the world, touched by the lives of those who relied on the streets. I was nervous, not from fear, but from that choking of emotions that comes with encountering the frail but enduring spirits whose lives are marked not by momentous events, but by the mere ability to wake up each day and navigate the misery. I knew the only way to make this exchange work was to stay real, connect on a real level, otherwise the boys would walk away or play us for all we were worth.

They didn’t look us in the eye, at first, answering initial questions by looking at one another or the ground. In the beginning, it was hard to understand their street Spanish, but the real ice-breaker came pretty naturally as I stumbled through my not-quite-fluent Spanish. The boys couldn’t resist looking up, curious as to who was so clumsily using their language.

When asked about the biggest challenge of street life, the boys all said it was trying to survive while staying out of the way. Street children are perceived as a plague and are routinely victimized by strangers, police, even other children. The more invisible they can be, the better for their safety. Street children are mirrors of life run amuck, and society would rather shatter the mirror than risk looking into it. The police are notorious for their brutal treatment of street kids. Police will beat the children, take their money, and send them out to collect more. It is a cold, mean world these kids encounter. Girls face even harder consequences; many are raped at young ages. Sexual promiscuity is not uncommon amongst these children. Some estimates suggested that 60% of La Paz’s street girls have children of their own or are pregnant, setting into motion a perpetual cycle of poverty and pain.

The discussion turned to school and we were dismayed to hear that none of these boys was able to attend. Survival demands all of their resources. Yet they are savvy. They knew of their country’s affairs and of worlds beyond their horizons. They spoke of child labor laws that blocked their way to working wages. And they weren’t yet afraid to dream. One wanted to be a doctor, to help other kids in his situation.

We asked about other boys we had seen while crossing town and were interrupted with clarifications that those were “huffers,” kids lost in a world of bags and glue bottles. We had seen them, propped against walls, too numbed to shiver or too dazed to care. Street children sniff paint thinner and glue for varying reasons. It helps keep them warm, dulls the pangs of hunger, and helps temporarily blot out the fears and pain that haunt their young lives. The ones we had passed were serious huffers, their brief lives close to an end. Passers by step around them like sidewalk debris. It is estimated that 97% of Latin America’s street kids sniff to some extent…girls, boys, pregnant teens.

The huffers rely mostly on a glue from the shoemaking industry. It’s a highly toxic adhesive that numbs the brain and eventually causes irreversible brain damage, in addition to organ loss and early onset diabetes. Advocates have called for a formulaic change to a water-based adhesive. Chile, Argentina, and Venezuela have already banned the use of the deadly solvent toxins. But Chile and Argentina are South America’s Europe; Bolivia and the other mountain states are primarily indigenous, where government actions have long ignored their well-being.

I noticed the boys adjusting their hoods, pulling their jackets up high, so finally asked if they were cold, if they needed warmer clothes. After moments of silence, one finally spoke, explaining they didn’t want to be recognized by the police or anybody else who might beat them. By day, many wear bandanas or ski masks while shining shoes or performing public tasks. This is their safety net of invisibility, the shroud that both protects and strips them of their identity.

With great insight, several of the boys told us their biggest fear. It is not the police, or the cold, or the constant hunger that gnaws at their thin bellies, but is instead the fear of getting older.

As kids, they can ebb and flow through the city with some success. But they can see the dead ends that face their older friends. No longer quick and agile, older street teens find themselves in more trouble than kids. Older beggars don’t have near the success that children do, and so their more desperate actions land them in more fateful fights and bigger trouble. They quickly find themselves unable to meld into the adult fabric that surrounds them. With little work opportunity for them beyond the informal sector, the spreading coca / cocaine trade calls temptingly. America’s addiction to cocaine opened vast networks of opportunity for peasant farmers and underemployed youth in Latin America. And Colombia’s scourge of narco-vice successfully infiltrated Peru and Bolivia, their jungles presenting perfect growing climates for farmers long mired in poverty.

Most disconcerting, I heard later, is that cocaine is moving much more actively toward the younger kids of the streets, not just to the north. As northern borders continue to tighten, local growers want to develop an internal market, using the street kids as vendors and rewarding them with freebie samples of their own to hook them. Lack of available bolivianos used to keep the kids on a budget of glue and thinner, but they are slowly getting sucked into this larger scheme and will potentially forfeit their lives for a bag of something intended for the U.S.

Malnutrition still haunts the children, an inheritance from their mothers and one they pass on to their offspring. About twenty percent of the babies die before the age of three and disabilities are common. Government programs for health care are virtually non-existent.

In the Seventies, lots of early oil money hopscotched its way from OPEC countries to Western banks to a network called the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF). Western controlled-World Bank and IMF issued massive amounts of loans to developing countries, grossly misrepresenting development potential and saddling countries with adjustable rate loans. When financial calamity gripped the world in the Eighties and sent interest rates skyrocketing, these financially strangled countries were forced into additional “Rob Peter to Pay Paul” loans. With those loans came strings attached, one of which was the curtailment of spending on health, education, and welfare programs. Many of the countries have still not rid themselves of this choking debt, and La Paz’s malnutrition and lack of health education stand as a remnant of this spectre.

The young kids are conflicted; invisible for survival, they long to be seen and yearn for nurturing. But cut off by parents who failed them, they are distrustful of nearly all adults. Many ignore the programs and shelter offered them, so angered and disillusioned are they by betrayal in their infancy that steel fences guard their emotions. The voids they are forced to call home know nothing of love and caring. These kids have been molded into something unnatural – neither child nor adult.

“Where do you sleep?” became our eventual query. They walked us a few blocks east and pointed down a darkened street toward the river, with a caution that we definitely shouldn’t go down there because it wasn’t safe. I read later that the river is filthy, one of the dirtiest in the world. The sewage offers some warmth while also providing some safety from those who might do them harm. When they can, they sleep curled up with street dogs. Blue and green tarps provide occasional shelter, along with metal scraps, black plastic, and cardboard. Many others sleep in doorways, on streets, or wherever their exhausted bodies land them.

Local governments don’t have the resources to address these issues, and national governments lack the will. The burden falls on NGO’s and private agencies. La Paz has some excellent programs, offering transitional housing, tutoring, counseling, minimal health care, and job training. But many programs can only deal with about ten kids at a time, barely getting a few kids off the street before the next batch is born.

This is a pandemic, repeated throughout the developing world. There is much that could be done, from government pressure on the police to free clinics and from single-parent assistance to birth control help, but each step takes money and will.

Our boys were still young enough to laugh and wily enough to be alive. We did not walk away in sadness. Invisible as they may be, they are waiting to be seen. In seeing them, we are gifted with seeing ourselves.